This is another of those slightly confusing

points when it comes to the classification system for plants. As

usual, there is a technical/scientific definition and then there is

the way terms are used by the gardening public.

This is another of those slightly confusing

points when it comes to the classification system for plants. As

usual, there is a technical/scientific definition and then there is

the way terms are used by the gardening public.

The confusion comes in the usage of the terms

Variety and Cultivar. Often, the average gardener uses these terms

interchangeably as if they mean the same thing. Technically, they

are quite different. A variety, often called a botanical variety,

refers to a naturally occurring change in a wild population of a

species.

For example, in the olden days, honeylocust

trees all had nasty, sharp thorns. Then one day, someone was walking

through the woods or nursery and saw a honeylocust tree that did not

have the thorns. They took some seeds or cuttings and starting

growing this oddball plant which, being thornless, is much more

desirable for home landscapes.

The genus and species for honeylocust is

Gleditsia triacanthos. The thornless variety is named Gleditsia triacanthos var.

inermis. The term inermis

means thornless. Notice that the abbreviation var. for variety is

not italicized nor would it be underlined if hand written. It may

also be dropped from the name so it could be listed merely as

Gleditsia triacanthos inermis.

When many people use the term "variety" when

talking about their landscape plants, what they are really talking

about is the "cultivar". This term refers to a cultivated variety.

It implies that human beings took a plant that varies from the

species i.e. a botanical variety, and have cultivated and propagated

it in the nursery. While it is true that some of these plant

variations did, in fact, occur in the wild, most of them come about

through controlled hybridizing or selections of nursery grown

plants.

When many people use the term "variety" when

talking about their landscape plants, what they are really talking

about is the "cultivar". This term refers to a cultivated variety.

It implies that human beings took a plant that varies from the

species i.e. a botanical variety, and have cultivated and propagated

it in the nursery. While it is true that some of these plant

variations did, in fact, occur in the wild, most of them come about

through controlled hybridizing or selections of nursery grown

plants.

A cultivar name is always capitalized and

enclosed by single quotation marks. For example, Hosta 'Gold

Standard' would be the correct form. In some cases, the entire

species name is includes such as in Hosta sieboldiana 'Elegans'.

Once the fact that the plant you are talking about is a hosta by

previous reference nearby in the document, you can refer to the

plant as simply, H. 'Gold Standard'. However, if you are also

talking about

Hemerocallis or

Helleborus at the same

time, it should be Hosta 'Gold Standard' to avoid confusion.

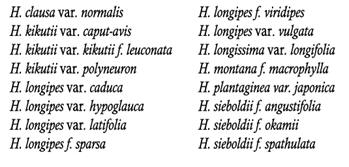

Schmid (1991) identified 16 significant

botanical varieties or forms of hostas. These plants represent

slight deviations from the species type that were found in the wilds

of Japan, Korea or China. A form or forma is a slight variation of a

botanical variety. Who knows, someday in the future, a taxonomist

might declare one or more of them to actually be new species. Stay

tuned.

Botanical varieties or forms (in Latin,

forma) defined by Schmid (1991) include:

Another area of confusion sometimes occurs when

using the term clones. Clones are plants that have been reproduced

asexually through cuttings, divisions or

tissue culture

and not from

seed. They are simply pieces of the original plant and are

genetically the same plant even though there may be tens of

thousands of them in gardens around the world.

Clones can be a cultivar but not all cultivars

originate as clones. Many cultivars come about as the result of

cross breeding plants and growing them from seeds. These seedlings

will contain genetic variations from the parent plants and are,

therefore, not clones. Of course, once a seedling is selected and

named as a cultivar, it will be propagated by asexual means and the

resulting plants are all clones of the original seedling plant. Hope

that isn't too confusing.

Clones can be a cultivar but not all cultivars

originate as clones. Many cultivars come about as the result of

cross breeding plants and growing them from seeds. These seedlings

will contain genetic variations from the parent plants and are,

therefore, not clones. Of course, once a seedling is selected and

named as a cultivar, it will be propagated by asexual means and the

resulting plants are all clones of the original seedling plant. Hope

that isn't too confusing.

Mr. PGC Link: HostaHelper

listings of over 13,300

Hosta Cultivars...

Each plant genus has rules for what constitutes

an acceptable cultivar name. The American Hosta Society follows the

International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP)

guidelines when it comes to approving names for new cultivars being

registered. These guidelines are very detailed and deal with such

items as proper formats, types of words to used in a name,

number of

words and a bunch of other factors. In the end, the goal is to

have a single, unique and non-confusing name for a particular hosta.

number of

words and a bunch of other factors. In the end, the goal is to

have a single, unique and non-confusing name for a particular hosta.

As you get more familiar with the world of

hostas, you will notice that certain cultivar names will seem very

similar. They may all contain a key word or follow a distinctive

pattern. Certain hybridizers or cultivar originators like to have a

"brand" name associated with their introductions. These "Series"

hostas account for a large number of the cultivars available today.

Perhaps the most common one is the "Lakeside" Series of hostas

originated by

Mary Chastain of Tennessee who introduced over 180

cultivars almost all with the first name Lakeside.

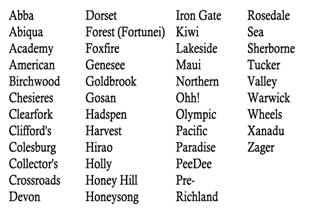

Zilis (2009) compiled the following list of

Series hostas. Note that, in a few cases, one person may have the

vast majority of cultivars in a Series but other hybridizers may

have named a cultivar or two that also use the key word involved.

Mr. PGC Link: HostaHelper lists of

Series Hostas...